Malnutrition is a condition that occurs when a person does not get enough nutrients.

Severe malnutrition is both a medical and social disorder. Malnutrition mainly affects children under five in developing countries and results in poor health. The malnourished child will also perform poorly at school and will be a less productive adult in the future.

Causes of malnutrition

They can be classified as root causes, underlying causes and immediate causes.

Immediate causes of malnutrition are:

Types of malnutrition

Chronic protein-energy malnutrition is manifested by stunting (short height or length) for age. Stunting occurs as a result of lack of food, or illness (Stunting indicates chronic malnutrition)

Acute protein-energy malnutrition is the term used to cover both moderate and severe wasting and nutritional oedema or kwashiorkor.

Micronutrient malnutrition or deficiency is the deficiency of the recommended amounts of essential vitamins and minerals. The child may not be eating enough of the recommended amounts of specific vitamins (such as vitamin A) or minerals (such as iron).

Anemia is one of the micronutrient deficiencies that is the lack of iron in the foods. A child can also develop anaemia as a result of:

Checking the sick child for malnutrition and anaemia

All children who are brought to the health post (visited at their home) for their complaint of acute illness, the health extension worker should check for malnutrition and anaemia. Since mother may bring her child to the health post because the child has an acute illness and specific complaints may not complain malnutrition. A sick child can be malnourished, but the child's family may not have realised the malnutrition as illness.

LOOK AND FEEL:

Children less than 6 months:

Children aged 6 months or more:

Look for palmar pallor:

Checking for visible severe wasting in infants less than six months of age

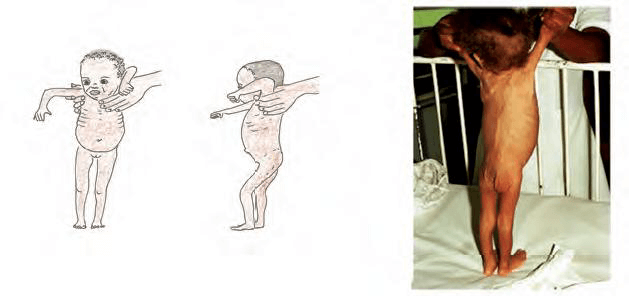

An infant with visible severe wasting has marasmus; it is a form of severe malnutrition. Marasmus is characterised by the wasting of muscle mass and the depletion of body fat stores. It is the most common form of protein-energy malnutrition and is caused by inadequate intake of all nutrients, but especially dietary energy sources (total calories). Physical examination findings include:

Visible severe wasting (Figure 7.1, below) can be assessed by looking at the face, the ribs, arms, the legs and the buttock. Remove the child's clothes for observation. Look to see if the outline of the child's ribs is easily seen. Look at the child's hips. They may look small when you compare them with the chest and abdomen. Look at the child from the side to see if the fat of the buttocks is missing.

When wasting is extreme, there are many folds of skin on the buttocks and thighs. It looks like the child is wearing baggy pants. The face of a child with visible severe wasting may still look normal. The child's abdomen may be large or distended.

Kwashiorkor. Kwashiorkor is characterised by marked muscle atrophy with normal or increased body fat. Pure kwashiorkor is characterised by inadequate protein intake in the presence of fair to good energy intake. Anorexia is almost universal. Physical examination findings include:

Intermittent periods of adequate protein intake restores hair color, resulting in alternating loss of hair color interspersed between bands of normal pigmentation.

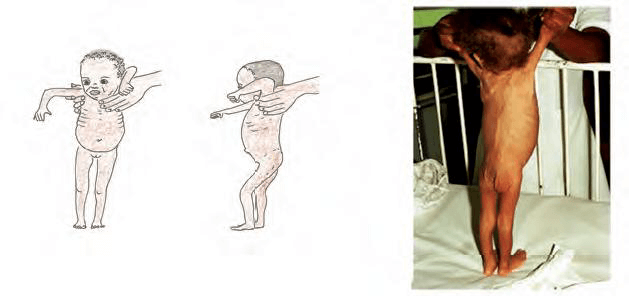

Measure the mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC)

For children aged six months or more, the most feasible way to determine wasting or acute malnutrition is by measuring their mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC). A MUAC of less than 11.0 cm indicates severe acute malnutrition.

Steps of MUAC measurement:

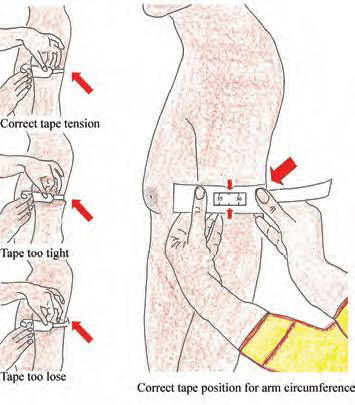

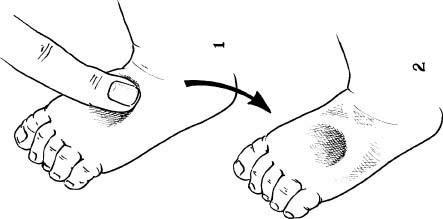

Look and feel for edema of both feet

A child with oedema of both feet may have kwashiorkor. Kwashiorkor is characterised by marked muscle atrophy with normal or increased body fat. Pure kwashiorkor is characterised by inadequate protein intake in the presence of fair to good energy intake. Anorexia is almost universal

To determine the presence of oedema, press gently with your thumb on the topside of each foot for at least three seconds a depression will occur.

Assessing appetite

For a child aged six months or above has a MUAC less than 11 cm or pitting oedema of both feet and has no medical complications, assess the child's appetite.

In a child who is 6 months or older, if MUAC is less than 11 cm or if oedema of both feet and has NO medical complications, assess appetite.

How to do the appetite test?

Passed appetite test:

Failed appetite test:

The appetite test should always be performed carefully. Patients who fail their appetite tests should always be offered treatment as in-patients. If there is any doubt, then the patient should be referred for in-patient treatment until the appetite returns.

| Appetite Tet: This is the minimum amount of RUTF that malnourished patients should take to pass the appetite test | |||

| RUTF (Plumpy Nut) | BP 100 | ||

| Body Weight (Kg) | Sachet | Body weight (Kg) | Bars |

| < 4 | ⅛. - ¼ | < 5 | ¼ - ½ |

| 4 up to 10 | ¼ - ½ | 5 up to 10 | ½ - ¾ |

| 10 up to 15 | ½ - ¾ | 10 up to 15 | ¾ - 1 |

| > 15 | ¾ - 1 | > 15 | 1 - 1 ½ |