7.2 Techniques of spinal anesthesia

It is difficult to teach a technique by describing it. Only through experience can one obtain a “feel” for the technique. We will, however, cover some important material that will be helpful when administering spinal anesthetics. The technique of administering spinal anesthesia will include preparation, position and performing spinal anesthetic injection phases.

7.2.1 Preparation:

Preparation of equipment/medications is the first step. A full set of general anesthesia preparation with resuscitation equipments are required when ever spinal anesthesia is planned.

7.2.1.1 Pre anesthetic visit: Make a pre anesthetic visit and discuss with the patient options for anesthesia. Explain risk and benefits. Inform the patient about the following: despite sedation the patient may remember portions of the surgical procedure but should not feel discomfort, the patient may feel pressure sensations but no pain; the patient will not be able to move their legs, and the approximate length of time that the block will last. Premedication is often unnecessary, but if a patient is apprehensive, a benzodiazepine such as 5-10mg of diazepam may be given orally 1 hour before the operation.

7.2.1.2 Choose an appropriate local anesthetic: What local anesthetic should be used? Should it be a hypobaric, hyperbaric, or isobaric preparation? The duration of blockade should match the proposed length of the surgical procedure. Consider additives at this point. The addition of epinephrine may be considered to prolong and/or improve the quality of the block. Drugs used for spinal anesthesia listed in session VI

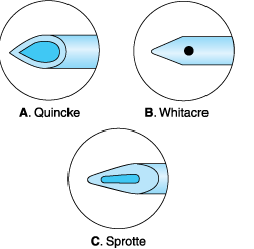

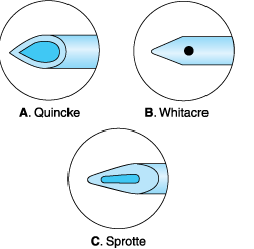

7.2.1.3 Choosing the appropriate spinal needle: Spinal needles are available in a variety of sizes, lengths, bevel types, and tip designs (Figure 7:1). Commonly, a 22 gauge needle is used in patients that are 50 years and older. A 25-27 gauge needle is used in patients that are less than 50 years of age. A smaller needle is used in the younger patient to decrease the incidence of post dural puncture headache. The removable stylet occludes the lumen and avoids tracking tissue into the subarachnoid space.

Figure 7:1 Tip of the spinal needle

Needles are cutting or blunt tipped.

A. The Quincke needle is a cutting needle

with end injection.

B. The Whitacre and other pencil-point

needles have rounded points and side

port for injection. It decreases the

incidence of postural puncture

headaches compared to cutting needles.

C. The Sprotte is a side injection needle

with a long opening. It has the

advantage of more vigorous CSF flow

compared with similar gauge needles.

This may also lead to failed blocks

since the opening may be partially

within the subarachnoid space, leading

to a partial dose of local anesthetic

being administered.

7.2.1.4 Spinal kit: Prepackaged spinal kits are normally used and can be custom made. If a prepackaged spinal kit is not available, assemble the following equipment:

- Sterile towels

- Sterile gloves

- Sterile spinal needle

- An introducer needle if using a small gauge needle (this can be a sterile 19 gauge disposable needle)

- Sterile needle to draw up medications

- Sterile 5 ml syringe for the spinal solution

- Sterile 2 ml syringe with a small gauge needle to localize the skin prior initiation of the spinal anesthetic

- Antiseptics for the skin (such as betadine, chlorhexidine, methyl alcohol)

- Sterile gauze for skin cleansing and to wipe off excess antiseptic at needle puncture site

- Single use preservative free local anesthetic ampoule. Local anesthetics from multi dose vials or those that contain preservatives should NEVER be used for spinal anesthesia. Ensure that the local anesthetic preparation is made specifically for spinal anesthesia.

7.2.1.6Prior to initiating a spinal block

- Intravenous Pre-loading (fluid bolus): All patients having spinal anesthesia must have a large intravenous cannula inserted and be given intravenous fluids immediately before the spinal. This helps prevent hypotension following the vasodilation which is produced by spinal anesthesia. The volume of fluid given will vary with the age of the patient and the extent of the proposed block. A young, fit man having a hernia repair may only need 500mls. Older patients are not able to compensate as efficiently as the young for spinal-induced vasodilation and hypotension and may need 1000mls for a similar procedure. If a high block is planned, at least a 1000mls should be given to all patients. Caesarean section patients need at least 1500mls. Crystalloids such as 0.9% Normal Saline or Ringer's lactate are most commonly used. Dextrose 5% should be avoided as it is not effective for maintaining the blood volume.

- Monitor: The patient should be attached to standard monitors including ECG, blood pressure, and pulse oximetry. Record an initial set of vital signs.

- Maintain sterility: At any point during the administration of spinal anesthesia, if sterility is questioned or contamination of equipment occurs, stop, and start over with sterile equipment.

7.2.2 Positioning: Proper positioning is essential for a successful block.

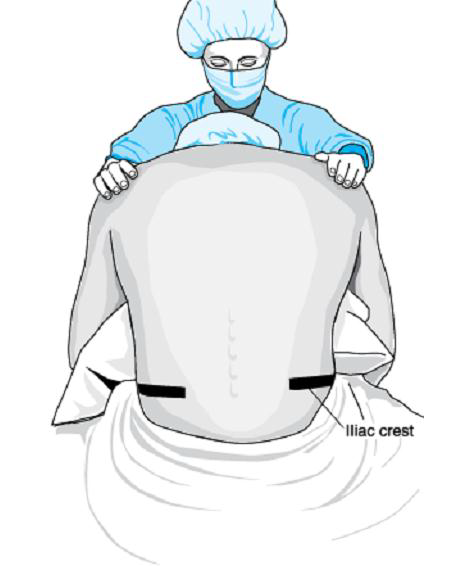

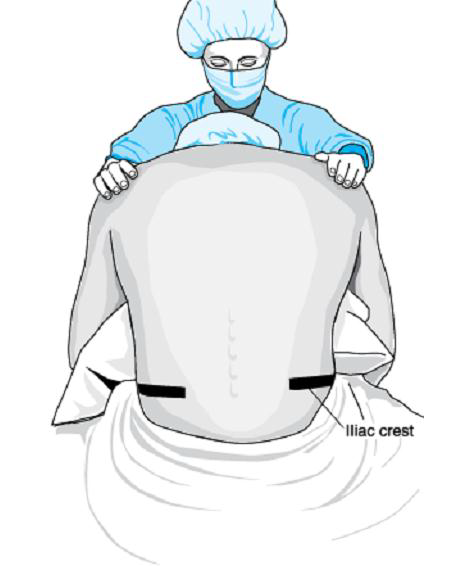

7.2.2.1 The sitting position

This position (Figure 7:2) encourages flexion and facilitates recognition of the midline, which may be of increased importance in an obese patient. When combined with a hyperbaric anesthetic, the sitting position favors a caudal distribution, the resultant anesthesia commonly being referred to as a “saddle block”, used for anesthesia of the lumbar and sacral levels (urological, perineal). Higher levels of anesthesia can be obtained if an appropriate dose of local anesthetic is administered, and the patient is quickly positioned to maximize the spread of local anesthetic. For a lower lumbar/sacral block (i.e. saddle block), leave the patient sitting for 5 minutes before assuming a supine position.

Figure7:2 Sitting position for spinal anesthesia

- The patient is placed with the buttocks near the edge of the table, and the legs over the opposite edge with the feet supported on a stool.

- The patient rests his elbow on his thighs, or folds his arms forwards over pillows, and flexes the neck.

- An assistant should support the patient from the front; every effort should be made to see that the back remains vertical & open up the lumbar vertebral space.

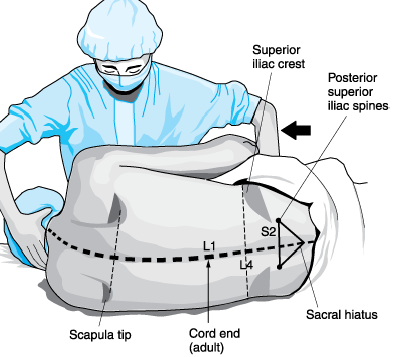

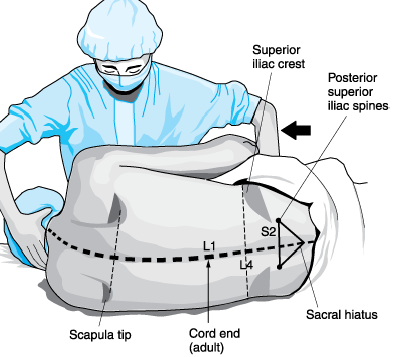

Figure 7:3 Lateral position for spinal anesthesia

This position enables the

anesthesia provider to safely

provide greater levels of

sedation. Ideal positioning

consists of having the back of

the patient parallel to the edge

of the bed closest to the

anesthetist, knees flexed to the

abdomen, and neck flexed

7.2.3 Performing spinal injection

- Identify the top of the iliac crest. A line drowns between the highest points of the iliac crests will cross the fourth lumbar spine or the space between the fourth and fifth spines. Other vertebral levels may be identified from this point and marked. The midline is noted by moving your fingers from medial to lateral.

- The spine is palpated and the patient's body position is examined to ensure that the plane of the back is perpendicular to that of the floor. The depression between the spinous processes of the vertebra above and below the level to be used is palpated; this will be the needle entry site. Remembering that the spinous processes course downward from the spine toward the skin, the needle will be directed slightly cephalad.

- Scrub, mask, glove up carefully and check the equipment on the sterile trolley.

- Draw up the local anesthetic to be injected intrathecally into the 5ml syringe, from the ampoule opened by your assistant. Read the label. Draw up the exact amount you intend to use, ensuring that your needle does not touch the outside of the ampoule (which is unsterile).

- Anesthetize (infiltrate) locally at the site of spinal needle entry, draw up the local anesthetic to be used for skin infiltration into the 2ml syringe. Read the label.

- Clean the patient's back with the swabs and antiseptic ensuring that your gloves do not touch unsterile skin. Swab radially outwards from the proposed injection site. Discard the swab and repeat several times making sure that a sufficiently large area is cleaned. Allow the solution (Iodine, alcohol) to dry on the skin.

- Locate a suitable interspinous space. You may have to press fairly hard to feel the spinous processes in an obese patient.

- If you are using an introducer (for a 24-27 gauge spinal needle), Inject 2-3 ml of local anesthetic (lidocaine 1-2%) to make a wheal under the skin with a disposable 25-gauge needle at the proposed puncture site and insert the introducer (18 -19 gauge) through the skin wheal. It should be advanced into the ligamentum flavum but care should be exercised in thin patients that an inadvertent dural puncture does not occur.

- If no introducer is used, the skin and soft tissues are fixed against the bony landmark by the second and third fingers of the left hand, which straddle the interspace. The spinal needle is inserted through the same hole in the skin that was used to perform the intracutaneous wheal and subcutaneous infiltration. The bevel of the spinal needle should be directed laterally, so that the dural fibers that run longitudinally are spread rather than transected.

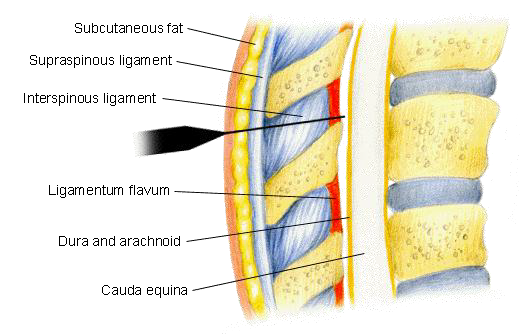

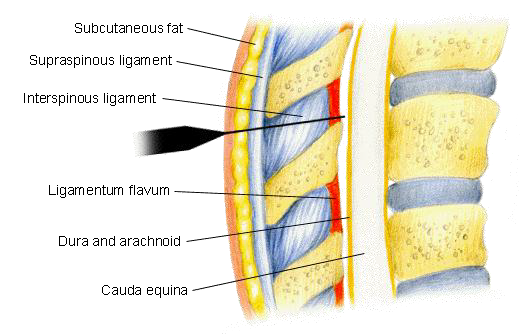

- As the needle penetrates the ligamentum flavum an obvious increase in resistance is usually encountered. When the spinal needle goes though the dura mater, a “pop” and slight discomfort is often appreciated. Once this pop is felt, the stylet should be removed from the introducer to check for flow of CSF (Figure 7:4).

Figure7:4 Anatomical structures that will be transversed

in midline approach include skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, ligamentum flavum, epidural space, and dura matter, arachnoid matter & subarachnoid space (CSF).

- Once CSF returns and clear, steady the needle with the hub of the spinal needle held firmly between the thumb and index finger of the left hand-the back of the left hand against the patient's back to prevent either withdrawal or advance of the spinal needle- the syringe containing the local anesthetic solution is firmly attached to the needle. Inject the local anesthetic at a rate of 0.2 ml per second. After injection aspirate 0.2 ml of CSF to confirm that the needle remains in the subarachnoid space. Before removing the spinal needle, one again performs aspiration and reinjection of a small amount of fluid to reconfirm that the tip of the needle is still in the subarachnoid space.

- The patient is then placed in the desired position; cardiovascular and respiratory functions are monitored frequently; and the analgesic level to pinprick or temperature level with alcohol is checked at 5-minute intervals until the desired level is achieved. The patient should be repositioned as necessary, according to the baricity of the injected solution to achieve this desired level; however, this must be accomplished within the "fixing time" of about 20 to 30 minutes for the local anesthetic.

7.2.4 Problems with the block and solutions

- If proper flow of spinal fluid does not occur, the needle is rotated in 90° increments until good flow is achieved. Occasionally if a small-bore spinal needle is being used, free flow of CSF will not be apparent. Gentle aspiration with a small, sterile syringe may then be used to obtain fluid. If no CSF appears then the stylet should be replaced. Assess the needle position. Is it at an appropriate depth? Is it midline or is off the midline? Being off the midline is one of the most common reasons that CSF does not come back. If off the midline, remove the needle and start over.

- If blood returns from the needle, wait to see if it clears. If it does not clear, reassess needle position. It may be in an epidural vein. Advance the needle slightly further to transverse the dura. If the needle is not midline, remove it and start over.

- The patient complains of sharp, stabbing leg pain. The needle has hit a nerve root because it has deviated laterally. Withdraw the needle and redirect it more medially away from the affected side. Never inject local anesthetic while the patient is complaining pain.

- If bone is encountered, reassess the patient's position and ensure the needle is midline. If bone is contacted early, the needle may be contacting the spinous process. Move the needle slightly caudad. If bone is contacted late, the needle may be contacting the lamina of the vertebrae. Move the needle slightly cephalad. Moving down an interspace may increase the chance of success since the intervertebral spaces will be larger.

- After unsuccessful attempts, consider converting to a general anesthetic. The more attempts, the more traumas, increasing the risk of a spinal/epidural hematoma.