7.1 Abdominal Trauma

The abdomen is frequently injured following trauma (Figure 7:1), is a major site for posttraumatic bleeding, and is difficult to evaluate and monitor clinically. Furthermore, uncontrolled hemorrhage is the major acute cause of death immediately following abdominal trauma. Patients involved in major trauma should be considered to have an abdominal injury until proved otherwise. Large quantities of blood (acute hemoperitoneum) may be present in the abdomen (e.g., hepatic or splenic injury) with minimal signs.

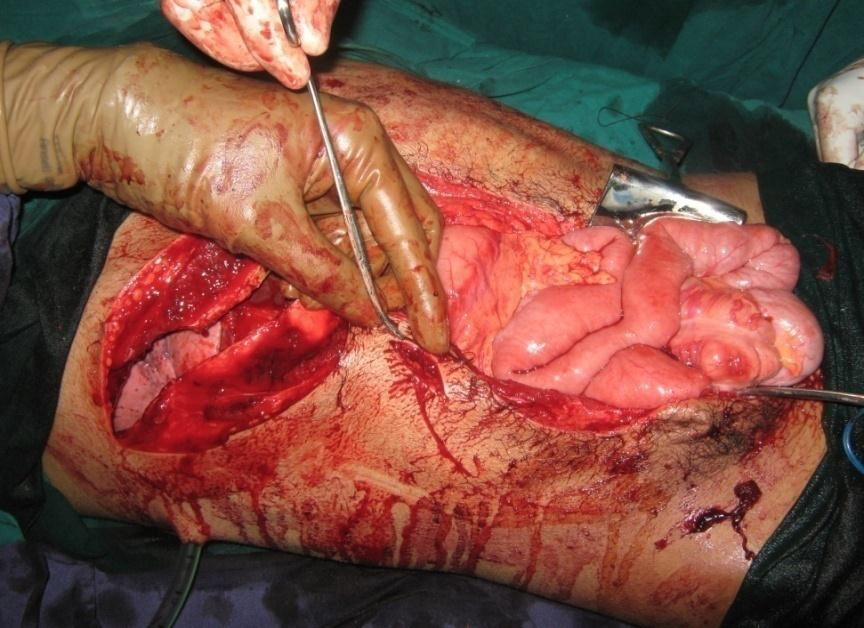

.png)

Figure 7: 1 Multiple trauma with abdominal wall injurry

7.1.1 Compartments of abdomen:

The abdomen can be divided into four anatomic compartments. The intrathoracic abdomen lies beneath the rib cage and includes the diaphragm, liver, spleen, and stomach. During exhalation (with both spontaneous breathing and positive pressure ventilation), the diaphragm often ascends to the third thoracic vertebra. Thus, a high association of intra abdominal injury occurs in patients with concomitant blunt or penetrating trauma to the lower chest. The hollow viscera (stomach, small and large bowel) are almost completely contained within the true abdomen, as is the omentum, gravid uterus, and the dome of the bladder (when full of urine). At the end of inhalation (during both spontaneous and positive pressure ventilation), the liver and spleen are pushed inferiorly by the diaphragm into the true abdomen. The pelvic abdomen is surrounded by the bony pelvis. Fractures and other trauma to the pelvis can injure these contents. Pelvic fractures often result in significant retroperitoneal hemorrhage. The retroperitoneal abdomen contains the great vessels, kidneys, ureters, pancreas, the portions of the duodenum, and some segments of the colon.

7.1.2 Types of abdominal trauma:

Abdominal trauma is usually divided into penetrating (e.g., gunshot or stabbing) and nonpenetrating (e.g., crush, or compression injuries).

7.1.1.1 Penetrating abdominal injuries (Figure 7:1) are usually obvious with entry marks on the abdomen or lower chest. The most commonly injured organ is the liver. Patients tend to fall into three subgroups: (1) pulse less, (2) hemodynamically unstable, and (3) stable. Pulse less and hemodynamically unstable patients (those who fail to maintain a systolic blood pressure of 80– 90 mm Hg with 1 –2 L of fluid resuscitation should be rushed for immediate laparatomy. They usually have either major vascular or solid organ injury. Stable patients with clinical signs of peritonitis or evisceration (The surgical removal of the abdominal viscera) should also undergo laparotomy as soon as possible. In contrast, hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating injuries who do not have clinical peritonitis require close evaluation to avoid unnecessary laparotomy. Signs of significant intraabdominal injuries may include free air under the diaphragm on the chest X-ray, blood from the nasogastric tube, hematuria, and rectal blood.

7.1.1.2 Blunt abdominal trauma is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in trauma, and the leading cause of intra-abdominal injuries. It is a compression of the abdominal cavity against fixed object solid organs, especially spleen and liver, are most commonly injured following blunt abdominal trauma. Injury to the diaphragm may permit migration of abdominal contents into the chest where they may compress the lung, producing abnormalities of gas exchange, or the heart, resulting in dysrhythmia and/or hypotension. Because the defect produced by blunt injury is larger than that resulting from a penetrating injury, migration of abdominal contents, which requires a defect of at least 6 cm in diameter, is also more common after blunt trauma.

7.1. 3 Overview of abdominal organ injuries

- The liver is the most commonly injured solid organ following penetrating trauma and the second most commonly injured organ following blunt trauma. Early death from abdominal trauma most commonly results from uncontrolled hemorrhage, and late death is most commonly attributable to sepsis. Clinical findings suggestive of liver injury following blunt trauma include fractures of the right lower ribs, pneumothorax, and right upper quadrant tenderness.

- The spleen is the most commonly injured abdominal organ following blunt trauma, and is also frequently injured following penetrating trauma to the left thorax or abdomen. Hypotension from hemorrhage is the most common initial finding. Splenic injury should be suspected in patients with left lower rib fractures, left upper quadrant tenderness, or left shoulder pain.

- Blunt pancreatic injury is usually due to an anteroposterior compression mechanism that crushes the pancreas against the vertebral column. Physical findings include burning epigastric and back pain, tenderness, or ileus.

- Renal injury is suspected with hematuria, fractures of lower posterolateral ribs, or flank pain and tenderness. It can bleed extensively into the retroperitoneal space.

- Injury to the stomach is commonly caused by penetrating trauma. The most common initial finding suggestive of gastric injury is blood via the mouth or nasogastric tube. Symptoms include the rapid onset of epigastric pain and peritonitis due to release of gastric contents into the peritoneum.

- Small bowel trauma may present with only vague generalized pain, with peritonitis after many hours. Duodenal injury may present with referred pain to the back.

- Colon injuries are common after gunshot wounds, and less so following blunt trauma. Symptoms of bowel injury are usually caused by spillage of intestinal contents, rather than from blood loss. Peritonitis occurs more frequently with colon injuries than from small bowel injuries because of the increased bacterial contamination.

- Patients with abdominal vascular injury usually present with profound hemorrhagic shock. The large-bore IV catheters are preferably located in the upper extremities to avoid fluid loss to the abdomen.

7.1 4 Surgical management and anesthetic consideration in abdominal trauma

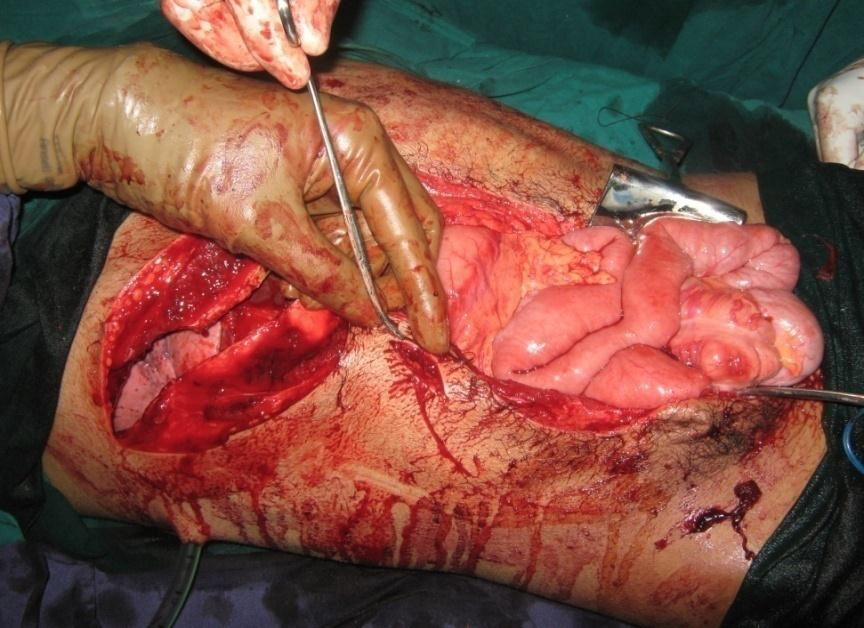

7.1.4.1 Explorative laparatomy: Explorative laparotomy (Figure 7:2) is done for diagnosis and definitive treatment of abdominal trauma.

Figure7:2 Extensive explorative laparatomy

Explorative laparatomy is done to:

- Locate and control hemorrhage

- Locate bowel injuries and control fecal contamination

- Identify injuries to other abdominal organs and structures

- Determine whether temporizing measures are most appropriate (i.e., damage control), or if definitive repair of injury should occur

7.1. 4.2: Preparation for anesthesia and surgery

- Preparation starts from initial assessment and resuscitation phase in which anesthetist should involve on survey of ABCs .

- Prepare for rapid sequence induction

- At least two large-bore peripheral IV cannula must be established and secured. Catheters are preferably located in venous systems that drain into the superior vena cava. Avoid femoral or saphenous venous catheters in patients with significant abdominal trauma. The utility of catheters draining into the inferior vena cava may be compromised should the inferior vena cava be clamped or packed during the surgical procedure. Profound hypotension may follow opening of the abdomen as the tamponading effect of extravasated blood (and bowel distention) is lost. Whenever time permits, preparations for immediate fluid and blood resuscitation with a rapid infusion device should be completed prior to the laparatomy.

- A quick evaluation of the patient‘s volume status can be made by measuring the blood pressure and heart rate, palpating the peripheral pulse, and assessing skin color and turgor and the quality of mucous membranes. Systolic pressure variation is a technique for gauging intravascular volume status that many anesthetists find very useful in trauma management.

- A nasogastric tube (if not already present) will help prevent gastric dilation but should be placed orally if a cribriform plate fracture is suspected.

7.1.4.3 Induction and maintenance

- Besides physiologic stability, analgesia and amnesia should be provided once the patient‘s hemodynamic status becomes stable enough to tolerate anesthetic drugs.

- Comatose patients, those in severe shock, and especially those in complete cardiopulmonary arrest on admission, require nothing more than oxygen and possibly a neuromuscular blocking drug until the patient‘s blood pressure and heart rate rebound enough so that anesthetics can be added. Awake traumatized patients demonstrating signs of hypovolemia are generally best induced with etomidate, 0.1–0.2 mg/kg or ketamine 0.5 – 1mg/kg, because thiopental and propofol may cause profound hypotension in hypovolemic patients.

- Traumatized patients should not receive propofol, thiopental, or other drugs with negative inotropic or vasodilator properties for induction. Anesthesia can be maintained with inhalational vapors or with intravenous drugs such as ketamine, with opioid supplementation as necessary. Ketamine can be used as IV maintenance. There are no absolute contraindications of any volatile drug for abdominal trauma. All volatile anesthetics produce dose-dependent depression of myocardial contractility. halothane maintains blood pressure better at the same minimal alveolar concentration

- Spinal anesthesia is contraindicated in the unstable abdominal trauma patient because it is impractical (the patient may not be able to assume the lateral or sitting position for drug placement), takes time to set up, and can result in several deleterious side effects, such as sympathectomy-mediated hypotension, local anesthetic-induced seizures, total spinal anesthesia, or cardiac arrest.

- As with all patients undergoing abdominal surgery, muscle relaxation facilitates exposure during exploratory laparotomy for trauma. No particular neuromuscular blockade drugs are contraindicated in abdominal trauma, unless hepatic or renal insufficiency is present

- Massive abdominal hemorrhage may require packing of bleeding areas and/or clamping of the abdominal aorta until bleeding sites are identified and the resuscitation can catch up with the blood loss. Prolonged aortic clamping leads to ischemic injury to the liver, kidneys, intestines, and lower extremities.

- Progressive bowel edema from injuries and fluid resuscitation may preclude abdominal closure at the end of the procedure. Tight abdominal closures markedly increase intra abdominal pressure that can produce renal and splanchnic ischemia. Oxygenation and ventilation are often severely compromised, even with complete muscle paralysis. Oliguria and renal shutdown follow. In such cases, the abdomen should be left open (but sterilely covered —often with intravenous bag plastic) for 48 –72 h until the edema subsides and secondary closure can be undertaken.

.png)

.png)